The frontlines between Taliban

and Northern Alliance forces had been drawn

for nearly three years along the Panjshir Valley, with the Taliban

holding areas in and around Kabul.

What the planners didn’t expect was the pinpoint of the close

air

support (CAS)

called in by Combat Controllers! Sergeant Calvin was the first Air

Force

Special Tactics to be attached to a U.S. Army Special Forces team

during this

operation. “We arrived in country around mid-October and was

the

only team

operating behind enemy lines for the first two weeks,” said

Calvin. “I have worked with SF’s in the

past and knew several of them from previous scuba training, so we came

together

quickly as a unit.” “We knew what our mission was

–

to help the Northern Alliance break through the Taliban lines and

liberate the capital.

|

The first day of the

operation would signal the start of what is reported to be the longest

sustained close air support operations conducted by Combat Controllers.

“We set

up an observation post in a mountain ridge overlooking the Taliban. The

valley

was literally filled with enemy tanks, personnel carriers and military

compounds. Working with the Northern Alliance

leadership, the target was selected – a command and control

building,” said

Calvin. “I called in the first CAS and a U. S. military

fighter arrived over

the area and dropped his ordnance and hit the building.”

That first strike not only

made an impression on the Americans, it made an impact on the Northern

Alliance forces working with this Special Operations Force (SOF) team.

“I wouldn’t say they mistrusted us initially. But

there was a certain sense

they weren’t sure how we could help them. After that first

CAS run, the wall

was broken and they seemed to realize we were there to help

them.”

|

As he and the team continued

the CAS calls, the resistance from the Taliban forces waned and

Northern Alliance gained ground. Then, as Northern Alliance began its

offensive, the enemy struck

back! “We were on top of a two-story building when they began

attacking. The

gunfire was intense. Then, they turned the guns on us. It was like

large,

flaming footballs flying at out position. The buttons on my uniform

were

getting in the way of me getting low enough. All I kept thinking was I

needed

aircraft. I grabbed the radio and called for immediate CAS.”

As the SOF team got down on

the roof for cover, a Northern Alliance

officer moved over to the Controller’s area. The officer

pushed in front of

TSgt Calvin, shielding him from the attack. Later, through an

interpreter, he

told the Controller why he did it. “He said if something

happened to him, he

knew someone else would step in to take his place in the fight. But if

something happened to me the planes could not come and destroy the

targets.”

The aircraft did come –

U.S.

Navy and Air Force fighters and bombers – and the offensive

continued. The next

day, 25 days after the first call for ordnance, the Northern Alliance

moved into the capital. After ensuring the city was

secure, the SOF team headed to the American Embassy that had been

evacuated in

1989. Before fleeing the city, the Taliban had used the building as a

staging

area.

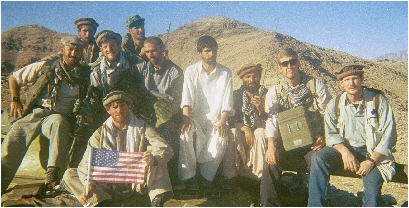

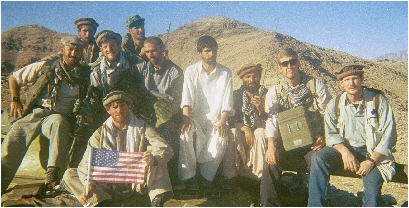

“We gained access

and one of

the first things I saw was an American Flag. It was on top of a pile of

straw.

Someone had tried to destroy it; the straw burnt and there were ashes

all over

the flag. When I picked up the flag, it was untouched – not a

burn mark on it.

With the help from a teammate I secured the flag by carefully folding

the Stars

and Stripes. I present that flag to my unit after I got back to the

States.

|

“It was amazing. It

was a

great feeling knowing we’d made the mission happen, and made

it happen in 25

days. I’ve trained what seems my whole life for the chance to

do a mission like

this, one that tests your skills and training. I said it before; we did

this

mission for America.”

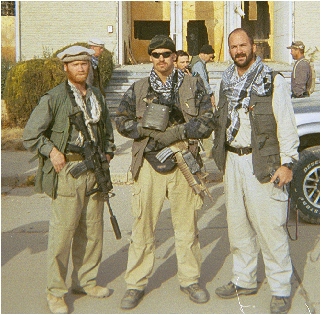

While his SEAL teammates

worked in the quiet mode, SSgt Eric took the lead in making all the

noise. He

was one of two Combat Controllers embedded with the SEAL’s

during operation

Enduring Freedom.

Climbing around the mountains

of eastern Afghanistan,

the SOF team was tasked with a sensitive exploration mission to search

and

secure caves in the Zawar Kili area of the country. “My

mission was to handle

all the close air support calls and provide the ground-to-air interface

between

the team and aircraft.” “Our team was tasked to

search known or suspected

Taliban and Al Qaeda compounds, including more than 50 caves and above

ground

sites.”

He and his teammates

were

flown into the region in helicopters during January. “We were

supposed to be in

the area for about 10 hours, and it turned into a nine-day

mission.” The

exploitation began about mid-point of a valley, with the joint team

setting off

on foot patrol. “We walked up and down the mountainside

checking anything we

came across. Though the coalition forces had bombed the area before we

arrived,

we had no guarantees all the Taliban and Al Qaeda troops had fled.

“We treated

everything as hostile. With so many caves and tunnels to hide in, we

didn’t

take any chances. We had aircraft in our area in case I had to call in

emergency CAS or needed to pull out. The aircraft also kept an eye out

in front

and behind us for any moving vehicles or people.

Though the joint team

did not

find any people hiding in the caves, what they did find was a major

storage and

hiding area for Taliban forces. “Inside the tunnels we found

caches of

munitions, communication systems, fuel storage rooms, classrooms,

living

quarters and filing cabinets filled with paperwork. As each cave and

compound

was secured and vital information removed, the SEALS’s EOD

specialist would

blowup the larger munitions inside in an attempt to collapse the site.

“After

the first day, we went back and found the caves were not completely

destroyed.

|

|

The CAS I called in on the site were making an impact, but

not sealing the

entrances. Many of the caves were lined with concrete and steel. Our

team

commander told us to figure out how to make the sites

inaccessible.”

|

With no maps that reflected

all the caves, the task would fall to the extensive training we had in

land

navigation and CAS. “The first obstacles were the fact that

we didn’t have a

detailed map. When you’re talking a pilot on to a target, you

have to

understand from his perspective that the mountains and desert all looks

similar.” Relying on a compass, a GPS, notebook and pen they

set out on the

task of creating maps of the caves. “To get exact coordinates

and the layout of

the cave, we had to create a sketch for each site. It took hours of

pacing off

the inside and outside of the caves to get good data so we give exact

data to

the pilots. We gave each cave a number then plotted its height on the

mountainside,

noted any surrounding obstacles, then began pacing off the inside of

the

tunnels – the slopes, the direction it was dug in, the

turns… We tried a few

different bombing runs; bring the bombs in at different angles to get

the best

possible attack on the sites. After a few runs, we found the best

attack was to

crack the entranceway and then a second bomb to collapse the

site.” The

double-bomb drop worked perfectly. “The impact was

incredible. We had one run

that literally blew the cliff line down over the entrance. We secured

and

destroyed every cave, and ensured they would be inaccessible to anyone

again.”

“We had to contend with the

mountainous terrain and the weather elements, as well the fact we went

in with

just enough supplies to last a day and would up staying nearly 10 days.

I have

done a lot of real world missions and training exercises in this type

of

scenario, so I was better prepared for the challenge. |

We went into the area

with just the essential gear, traveling as light as possible. Going as

light as

possible meant “rucking” up mountains with more

than 100 pounds of gear. We had

all the communications gear and air traffic control equipment needed to

do CAS

calls, as well as providing the ground-to-air interface with the

aircraft. Our

training in CAS and our land navigation skills helped ensure if the

Taliban or

Al Qaeda ever tries to gain access to those caves again, they need some

heavy equipment

just to find the front door.

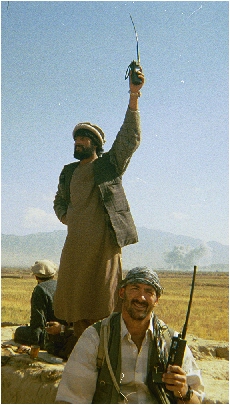

| MSgt Bart

Decker remembers

riding on horseback to the top of the highest peak south of Mazar-e

Sharif in

northern Afghanistan

in November, 2001 and watching the Taliban flee in pickups and

four-wheel

drives, their headlights illuminating the only road out of town to the

east. It

was almost too easy. Flicking on his GPS

receiver, Bart calculated coordinates for either end of the narrow

stretch of

highway and radioed them to B-52 bombers and F-16 fighters loitering

overhead.

Then he watched, horse by his side, as bombs rained down from the sky,

striking

the vehicles and killing their occupants with devastating precision.

Decker is

an Air Force Special Operations combat controller an unlikely

super-warrior.

His core skill is air-traffic control and his most potent weapon a GPS

receiver

available at the average electronic store. Yet, in a war driven by

precise

information about the Taliban and Al Qaeda targets, Bart and other

combat

controllers, embedded in Army Special Forces A teams, emerged as

pivotal

figures in the fusion of U.S. targeters on the ground with precision

strikes

from the air, the conflict’s most important tactical

innovation. |

|

An Afghan militia leader

who

has fought against the Russians and with the Americans said the

air-ground

coordination was the key to the victory by U.S.-led Northern Alliance

forces last year against Al Qaeda and the Taliban militia

that sheltered the terrorist network. “The people with

Special Forces controlling

the jets are very effective – they really know what they are

doing,” he said.

“It was American aircraft that broke the front line of the Al

Qaeda.”