In the vicinity of Gardez, in the eastern highlands of Afghanistan, Chapman's helicopter came under heavy machine-gun fire during insertion for a reconnaissance and close-air support mission. The helicopter sustained a direct hit from a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG), which caused Navy Petty Officer Neil Roberts to fall from the aircraft.

Though heavily damaged, the helicopter made an emergency landing seven kilometers away. Once on the ground, Chapman established communication with an AC-130 gun- ship to ensure the area was secure, while providing close air support coverage for the entire team. He then directed the gunship to search for the missing SEAL. He requested, coordinated and controlled the helicopter that extracted the stranded team and aircrew members. These actions limited the exposure of the aircrew and team to hostile fire.

"Without regard for his own life," his Air Force Cross citation reads, "Chapman volunteered to rescue his missing team member from an enemy stronghold."

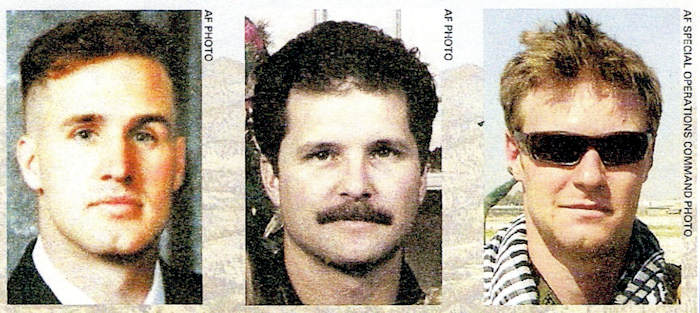

Shortly after insertion, the team made contact with the enemy. Chapman, a member of the 24th Special Tactics Squadron, engaged and killed two enemy personnel. He continued to advance, reaching the enemy position, then engaged a dug-in machine gun nest. While the rescue team came under enemy fire from three directions, he exchanged fire from close range with minimal cover until he died of multiple wounds.

"His engagement and destruction of the first enemy position and advancement on the second position enabled his team to move to cover and break enemy contact," his citation reads. "His Navy SEAL team leader credits Chapman unequivocally with saving the lives of the entire rescue team."

'Unusually Aggressive, Focused'

Lesser known than Green Berets, Army Rangers, Delta Force or Navy SEALs, battlefield airmen perform invaluable special operations for the Air Force.

"We're looking for the Type-A personality, unusually aggressive, focused," Tech Sgt. Jay Chambers, a pararescue- man and instructor, told USA Today. "We need somebody who's always wanted to succeed. People who don't want to do ordinary things."

Battlefield airmen are specially trained volunteers who provide unique expertise in land combat environments, often in hostile territory. This small, mostly enlisted group provides a link between air and ground operations.

These men (women are not at this time accepted) conduct ground operations to assist, control, enable and execute air and space power. This includes surveillance, weather forecasting, airfield surveying, air traffic control, directing air strikes, airdrop marking, trauma care and personnel recovery.

Various battlefield airmen specialties are sometimes combined into special tactics teams that work independently or with other services. The 720th Special Tactics Group comprises more than 800 battlefield airmen in six squadrons.

Nearly half of battlefield airmen are assigned to tactical air control parties (TACPs), training and deploying with Army units to advise ground commanders on air power and to direct air strikes.

"The biggest part of our job is the liaison function, helping the Army understand Air Force talk and the Air Force understand Army talk," said

Staff Sgt. Zachary Atkinson, a 342nd Training Squadron TACP instructor. "We make sure the pilots understand what's going on on the battlefield and the ground commanders understand what's going on in the air."

Combat Controllers Manage Airfield Operations

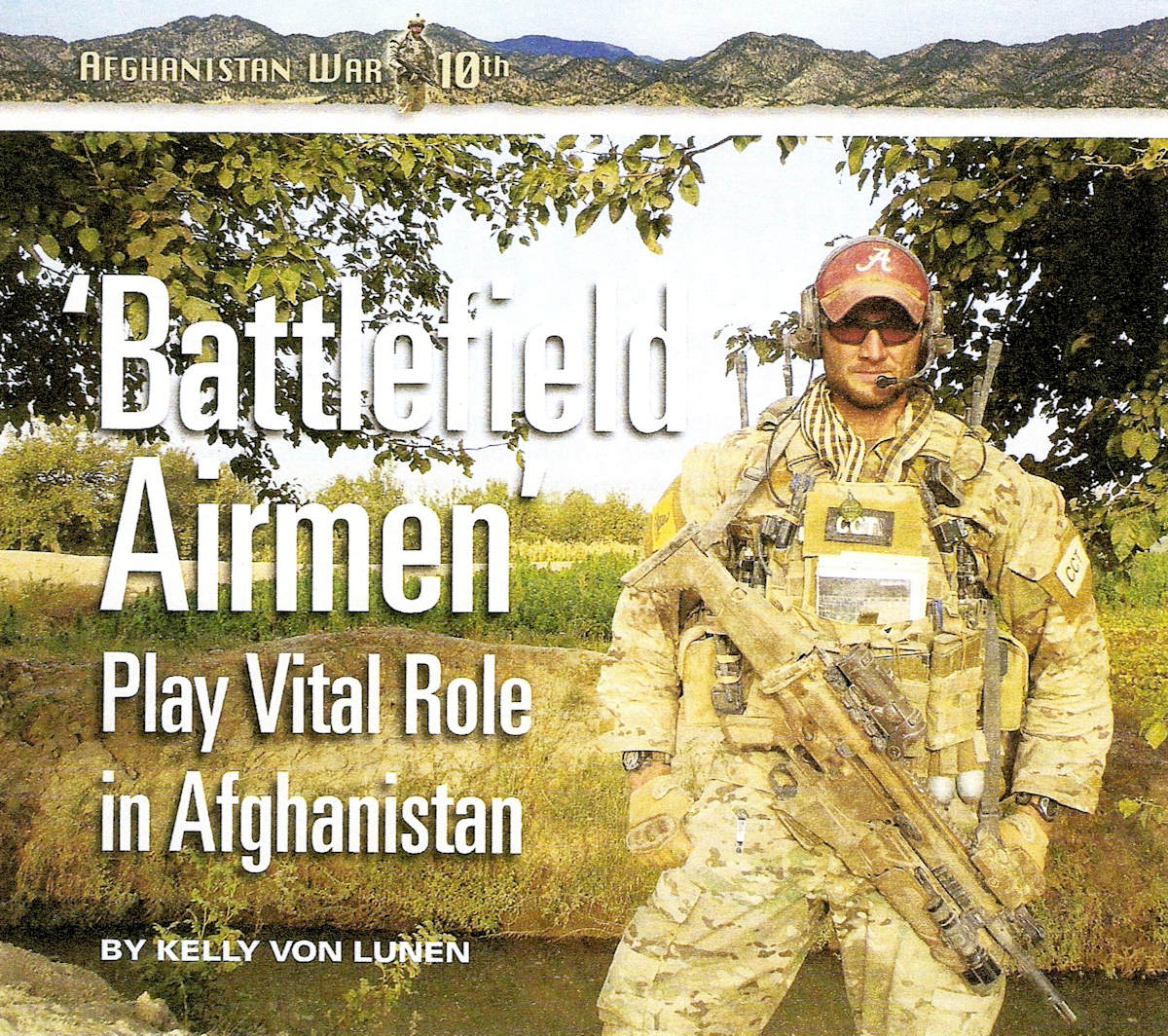

Staff Sgt. Zachary J. Rhyner of the 21st Special Tactics Squadron received the Air Force Cross for actions on April 6, 2008, during his first deployment to Afghanistan.

Working with some 100 Army Special Forces and Afghan soldiers, Rhyner's job during a six-hour fire- fight was to call in air support in the Shok Valley. He controlled more than 50 attack runs, with many of the strikes within 100 meters of his position.

Climbing from the valley into a village where they hoped to capture high- value targets, they met an ambush from some 200 insurgents.

"We were caught off guard as 200 enemy fighters approached," fellow Combat Controller Staff Sgt. Rob Gutierrez said. "Within 10 minutes, we were ambushed with heavy fire from 50 meters."

More than half the Americans there that day were wounded, but none were killed. The Air Force estimated that 40 enemy fighters were killed and 100 wounded.

Gutierrez also has been nominated for an Air Force Cross for his actions that day.

|

|||||||||

Combat Controllers deploy into hostile territory to direct paratrooper assault drops, identify potential aircraft landing fields, and conduct special operations to support Air Force and defense missions.

"The main reason I became a Combat Controller was for the mission opportunities," said Master Sgt. Ken Huhman, who served in Afghanistan with the 23rd Special Tactics Squadron in 2007.

They are trained to use demolitions to clear runways and to set up navigational aids. Moreover, as certified air traffic controllers, they can manage all airfield operations and local airspace, even in remote locations. Some Combat Controllers also direct close air support and combat search and rescue.

'Not One of Us Thought Twice'

Senior Airman Jason Cunningham earned his Air Force Cross two days before Chapman on March 2, 2002. Cunningham, a pararescue jumper (PJ) with the 38th Rescue Squadron, was working with Army Rangers in the Shah-i-Kot Valley.

On a mission to rescue a Navy SEAL, the helicopter he was aboard was shot down by an RPG. Cunningham dragged wounded troops across the line of enemy fire seven times. Though he was shot twice, he continued to treat patients. All of those he treated survived, but Cunningham died on Takur Ghar Mountain about an hour and a half before the medevac helicopter arrived.

PJs act as the surface-to-air link during personnel recovery. They are skilled in treating injuries when recovering personnel. They bring people out of difficult situations at any time of day in any terrain. PJs are proficient swimmers, expert riflemen, and masters of evasion techniques and land navigation.

Three PJs earned Bronze Stars for valor for their actions on June 3, 2010. Tech. Sgt. Jeffrey Hedglin, Staff Sgt. Asher Woodhouse and Tech. Sgt. Ryan Manjuck of the 58th Rescue Squadron landed amid a heavy firefight in the Arghandab River Valley and evacuated a wounded soldier. An hour later, they successfully evacuated two more soldiers from the same location.

"We knew it was going to be a hostile area with some increased danger, but not one of us thought twice about [ourselves]," Manjuck told Air Force Times.

"We knew we'd hop on the bird and go back out."

We're Weather Guys Second'

Special operations weathermen (SOWs) are involved in the planning of every special operations mission. SOWs are Air Force meteorologists trained to operate in hostile or denied territory. They gather, assess and interpret weather and environmental intelligence from deployed locations while working primarily with Air Force and Army special operations forces.

Of the 3,000 airmen assigned to Air Force weather units, only some 200 are SOWs. "We're special operations first, weather guys second," said Maj. Bob Russell, commander of the 10th Combat Weather Squadron.

These weathermen collect weather, ocean, river, snow and terrain intelligence, and integrate that into command and control and mission planning. They generate mission-tailored target and route forecasts. Additionally, SOWs conduct reconnaissance, collect upper air data, organize, establish and maintain weather data reporting networks. They determine meteorological capabilities overseas and train foreign special operations forces.

During wartime, SOWs often parachute behind enemy lines and travel with a platoon of soldiers. Their forecasting and observation tools fit in a rucksack that includes inflatable black balloons to calculate wind speeds and handheld digital gear to measure conditions on the ground. Whereas airplanes can maneuver through many types of weather, Army helicopters require an accurate weather forecast for safe flight.

"Dealing with helicopters, you have to be spot-on because they don't have the leeway that an airplane would have," Staff Sgt. Charles Williams of the 1st Weather Squadron told the Army News Service.

Disproportionate Casualties

The deadliest single incident so far in Afghanistan for battlefield airmen came on June 9,2010. Four pararescuemen— two of the 48th Rescue Squadron and one each of the 58th and 66th Rescue squadrons—were killed when their helicopter was shot down by an RPG near Forward Operating Base Jackson in the Sangin District.

As of July 18, 2011, 13 battlefield airmen (8 from the 720th STG) had been KIA in Afghanistan since 2001—31% of the total airmen KIA there. (One also had been KIA in Iraq.) Yet they comprise less than 1 % of theAir Force.